How much is the UK eating?

Using doubly labelled water to improve our understanding of the UK’s calorie intake.

The problem

We’re not very good at reporting what we eat. Evidence presented in Counting calories: how under reporting can explain the apparent fall in calorie intake (Behavioural Insights Team, Cabinet Office, 2016) shows that official estimates of the UK’s calorie intake, published by Public Health England (PHE), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) underestimate the UK’s calorie intake by between 20% and 35%.

It is important to understand how much we are eating to tackle the links between diet and ill health. Obesity increases the risks of Type 2 diabetes, strokes, heart disease and certain types of cancer. Treating obesity related ill-health in England cost the NHS an estimated £5.1 billion in 2014-2015.

Improving our official estimates is an important part of tackling obesity. So, over the last few months we’ve been working on the Evaluating Calorie Intake for Population Statistical Estimates (ECLIPSE) project. ECLIPSE focuses on exploring the underestimates in self-reported calorie intake measures, using biometric data to recalibrate data from surveys.

Why are we under-reporting what we eat?

Official estimates are based on the National Diet and Nutrition Survey which ask the respondents to complete a four day diary of their food intake. There are three main reasons why this is difficult.

- As individuals we aren’t very good at reporting our food intake accurately. This might be because:

- we don’t know what our food portion sizes are

- it might be difficult to know what the ingredients are, and the relative contribution from each ingredient, especially if we haven’t cooked the food ourselves

- we struggle to remember everything we ate

- and social pressure may make us inclined to leave out certain foods, or to say we have eaten less than we did.

- The four day period may not be very representative of what we eat over a whole year. How often we eat, and the variety of what we eat may change over the year (perhaps for many of us particularly over Christmas!)

- Translating food intake into calorie intake is difficult. The food recorded by the survey respondents has to be translated into data on its nutritional value. This is done by linking the food types to a database of thousands of foods, recipes and products. This is no small task, and the reference database has to be continuously updated to account for the ever-expanding selection of available foods. It’s a tall order for any reference dataset to represent the wide variety of food available to us.

Data science to the rescue!

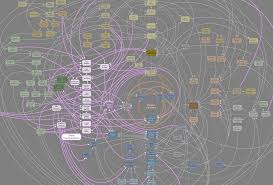

Data science techniques and tools can help us improve the accuracy of the official estimates, supplementing the social survey data. The data revolution looks set to transform dietary assessment methods which will enable scientists, dieticians, clinicians and medical researchers to better understand calorie intake, and so inform policies that help to drive improvements to our health by reducing dietary-related diseases. For example, food nutrition databases could be improved using automated data collection mechanisms that collect data from multiple sources to feed into a dynamic food reference nutrient database. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Composition Database is a good example of this in action. Data collection could be updated to use digital platforms improving response and quality. Administrative data sources could be analysed to further understand representativeness.

For this project, we focused on developing a better understanding of the under-reporting. We did this using doubly labelled water, collected from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey.

In doubly labelled water, the amount of heavy isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen are increased compared with normal tap water. The heavy isotopes have more neutrons than normal oxygen or hydrogen, but they still act in the same way. They are non-radioactive and so are safe to drink! This “labelling” of the water allows the metabolic rate to be measured over a period of time, which ultimately gives a measure of how many calories people expend. This should be the same as their calorific intake, and differences allow us to identify misreporting in the diet diary. A small sample size is used as it’s an expensive method, but it is an accurate method, which overcomes the challenges of self-reporting.

Using this data, standard statistical techniques can be applied, to predict the differences between the reported calorie intake from surveys, and the actual calorie intake. These can then be converted to weights to adjust self-reported measures, improving the accuracy of the larger survey estimates.

What’s next for ECLIPSE?

We think this is interesting and important work! If you do too, then look out for the full report, which will be published on the Data Science Campus web pages.